Computing is pop culture. […] Pop culture holds a disdain for history. Pop culture is all about identity and feeling like you’re participating, It has nothing to do with cooperation, the past or the future—it’s living in the present. I think the same is true of most people who write code for money. They have no idea where [their culture came from]. - Alan Kay

We have ignored cultural literacy in thinking about education. We ignore the air we breathe until it is thin or foul. Cultural literacy is the oxygen of social intercourse. - E. D. Hirsch Jr

To be culturally literate is to possess the basic information needed to thrive in the modern world. Computing cultural literacy is an overlapping but largely separate possession of basic information needed to thrive in today’s world of software and computing. Or is it needed at all? In 1993 Jeff Bezos was sitting somewhere in Seattle and watching internet traffic grow 230,000% in one year. Did he need to know about UNIX, the Morris Worm, and Ada Lovelace in order to start Amazon.com and become maybe the most successful software entrepreneur of all time? If one were to set down these ‘things to know’, would most programmers know them? Would you?

Cultural literacy is an idea taken directly from E. D. Hirsch Junior’s 1987 book, aptly titled Cultural Literacy. Hirsch Jr, a renowned education reformer, wanted the public to buy into great claims about knowledge-based literacy and the democratic, nation-building power of shared ideas. He lost the debate and his country’s institutions went other ways. In computing however, the debate has never been had. Alan Kay’s quote at the top is the one shot fired, as far as I know. He said that in a 2012 interview, and while he was clearly rankled, no one else cared to fight about it. Perhaps this field is too young, and does not yet have time for intro- and retro- spections.

Pop culture may, as Alan says, have a disdain for the past, but coders don’t shout a proud, rebuffing “we ain’t got no history”. Programmers tend to approach questions of providence and prior art as not so much unimportant but unnecessary. If you come across people in the street tearing money out of a clear blue sky, ask them where it came from. You’ll feel as a software historian may do, interrupting a party and asking if not for answers at least for someone to please take some notes.

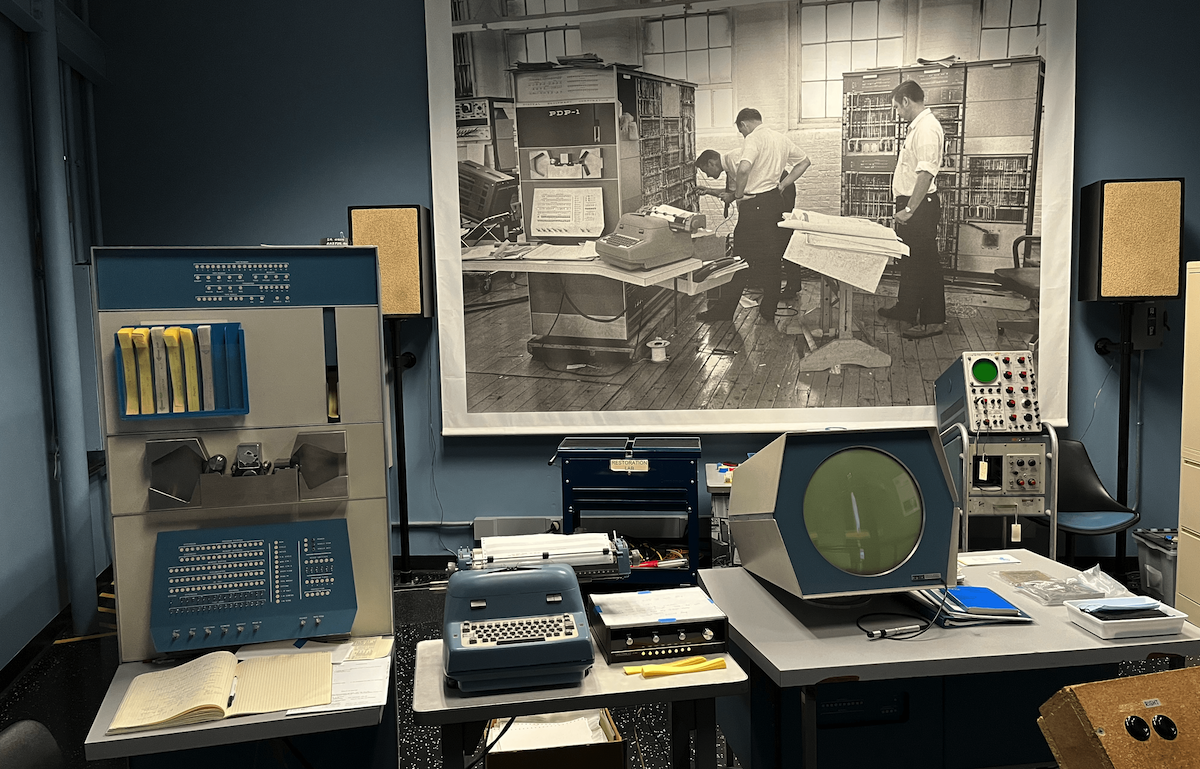

But I have found that I’m on Kay’s side. There is just so much back there, in the past. There’s radio-controlled torpedoes, Usenet, computers in their own room, booms and busts, brb and ttyl, lessons, less than 640K of RAM, and only 140 characters. And of course, people—a lot of people taking acid and soldering tools of enlightment; Turing award winners sitting alone in college offices writing tomes all come to love and never read; Turing, who you’ll know made an eponymous machine and an AI test and was gay, but that’s not enough to know; couples spending nights at the Microsoft office, one at a keyboard, one in a cot beside; people still right here, in old file systems used by billions, commenting things like “Error, skip block and hope for the best.”

Advancing cultural literacy is not revanchist. It does not want a rvtvrn to the old days when the term “software” sounded funny, and it’s not a homework assignment. Let’s even concede that no one really needs to know this stuff. But we should want to, because it’s just more fun, and with the knowledge we’ll do better work together. So…

lest a whole new generation of programmers

grow up in ignorance of this glorious past,

I feel duty-bound to describe…

… 400 essential names, dates, and concepts

Following the lead of Hirsch Junior’s original book, here’s an attempt at a list of essential names, phrases, dates, and concepts in the computing and software community. E. D. Hirsch Junior’s list was an absurd 5,000 items; here I bother with only 400.

As with the original list, “knowing” something implies familiarity but not expertise.

The original list was also made collaboratively, and so is this one! Our culture always moves. Thinking left-to-right, at the left we have what’s slipping out of view and at the right is what is entering the core but remains fringe. You can indicate left when you find something to be ‘too left’, that is, exiting our culture into the past. Indicate right for the opposite, when something is ‘too right’, or too new. You can also just trash an item.