Peter Norvig’s sixteen latency numbers, also popularized by Jeff Dean, are entering into the industry’s canon and acquiring even a little mystique as the typical developer’s distance from the L1 cache increases.

Thereabouts every year a new spin on the numbers blows up on HN and interrupts our forgetting curves. This refreshing encounter with the numbers is always welcome, but it’s unfortunate that these new editions exhibit maddening UI or offer extrapolated, wildly incorrect data.

I just like getting the original plaintext table. I read it, remember it, and then wonder: OK, what other numbers must I learn?

L1 cache reference ......................... 0.5 ns

Branch mispredict ............................ 5 ns

L2 cache reference ........................... 7 ns

Mutex lock/unlock ........................... 25 ns

Main memory reference ...................... 100 ns

Syscall on Intel 5150 ...................... 105 ns

Compress 1K bytes with Zippy ............. 3,000 ns = 3 µs

Context switch on Intel 5150 ............. 4,300 ns = 4 µs

Send 2K bytes over 1 Gbps network ....... 20,000 ns = 20 µs

SSD random read ........................ 150,000 ns = 150 µs

Read 1 MB sequentially from memory ..... 250,000 ns = 250 µs

Round trip within same datacenter ...... 500,000 ns = 0.5 ms

Read 1 MB sequentially from SSD* ..... 1,000,000 ns = 1 ms

Disk seek ........................... 10,000,000 ns = 10 ms

Read 1 MB sequentially from disk .... 20,000,000 ns = 20 ms

Send packet CA->Netherlands->CA .... 150,000,000 ns = 150 ms

Assuming ~1GB/sec SSD

With Anki spaced repetition you can nail these down quickly and never forget them. You’re done! But of course not. Where should we be if no one tried to find out what lies beyond.

The new numbers list!

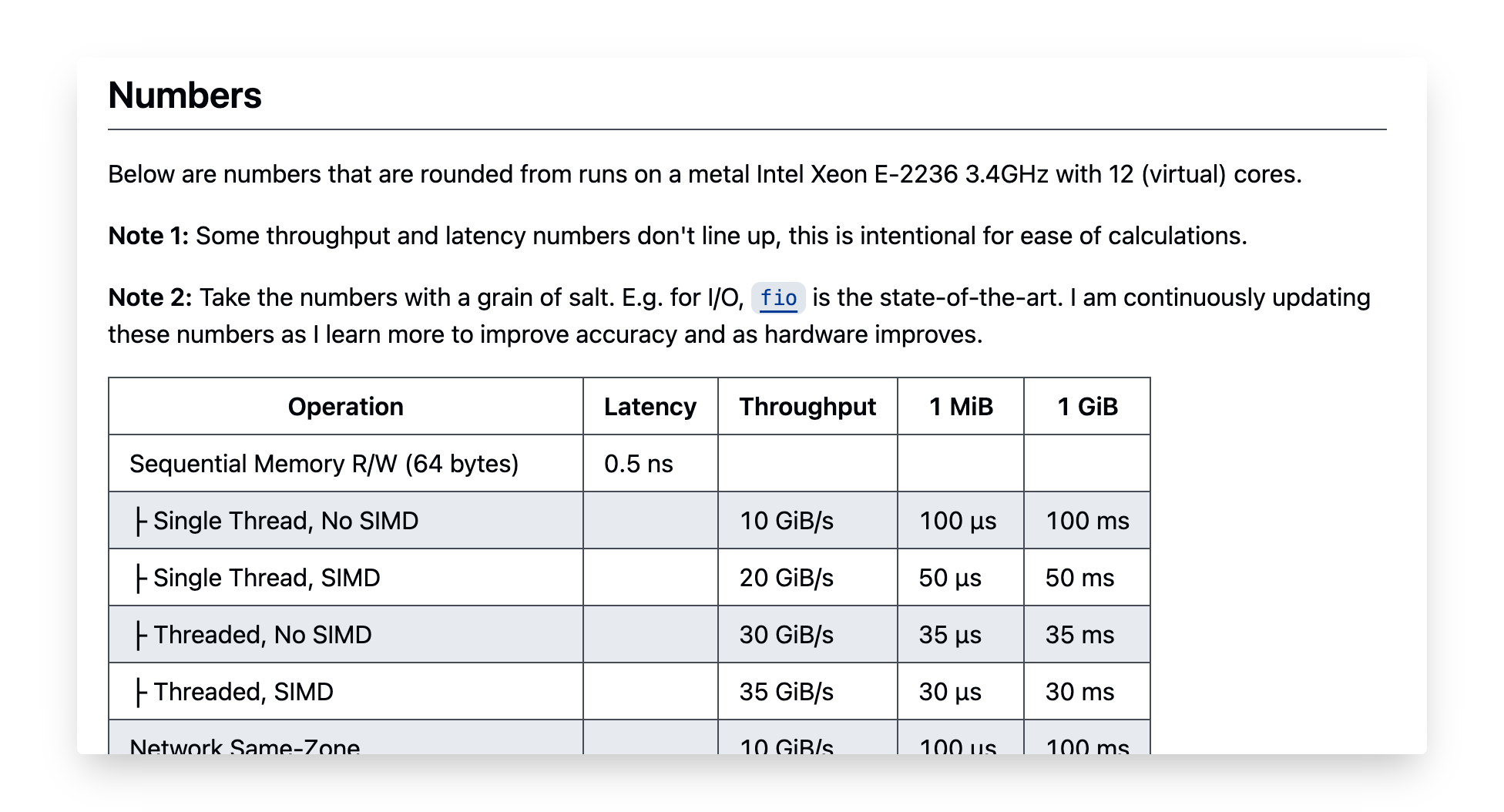

Whenever people share a version of Norvig’s original latency numbers I think they should really just share this Github repo: https://github.com/sirupsen/napkin-math.

It’s by Simon Eskilden, a gun former Principal eng at Shopify who now writes and sells a vector database. Unlike the original latency numbers list, this repository has a number of valuable features.

✔️ It’s up to date. Numbers are for contemporary hardware, algorithms, protocols.

✔️ It’s actively maintained. (I help from time to time.)

✔️ It’s tested, with new benchmarks using the excellent Criterion.rs library.

✔️ It’s referenced. (I found the references for the context switch number particularly interesting.)

✔️ It goes beyond latency, including throughput numbers and cost ($$) numbers.

✔️ It expands scope, adding numbers for cryptographic hashing, cloud services.

sirupsen/napkin-math is already far better than the original list. In fact, I’m going to try make this the 2025 “latency numbers every programmer should know” front pager. Let’s see how it goes.

Update: it got marked as dupe because it was posted 4 months ago. Alas.

Other numbers we must know (sooner or later)

In my day to day I’ve collected more numbers that I try to keep in memory with Anki flash cards. Some of them are a little peculiar.

Latency

| L1 cache reference (for comparison) | 0.5 ns | .0005 ms |

|---|---|---|

| blink | 100,000,000 ns | 100 ms |

| idle attention span | 20,000,000,000 ns | 20 s |

| one day | 86,400,000,000,000 ns | 86,400 s |

- A blink is an intuitive, human-oriented sense of a fast action. “Blink and you’ll miss it.” A number of human-computer interface elements aim for latencies in this range: frame refresh (~33ms), “perceptual processing” (100ms), reaction time (150-250ms).

- This is a personal guessimate I’m throwing out there because I’d love to get more serious information on the idle attention spans of engineers. For me, if I’m waiting on some process (e.g. compiling) and it doesn’t give me interesting output or indicate it will finish presently, I switch away to Slack or something. Although it’s fuzzy, I think this ~20 second boundary is the difference between

uvandpip. The former is always under it, and is loved, and the latter is rarely under it. - The length in seconds of one day is another human-oriented duration which is often handy to relate to software performance. When doing napkin math you can approximate it as 100,000 seconds and get quick, rough estimates of job processing time at human-scale.

Cost

| CPU core hour (for comparison) | $0.10 |

|---|---|

| “Fully loaded” engineer hour | $100.00 |

| Logging a line to Datadog | 1 second of CPU |

- The fully loaded cost of an engineer is their salary and stock compensation plus taxes, a benefits package, employer contributions to retirement, healthcare, that free soda your HR department loves mentioning in the job ads, etc. Here I’m using the cost of a reasonably well paid engineer in a tech hub such as San Francisco. If you work somewhere like OpenAI it’s probably closer to $200, but $100 is both more typical and a nice round number. This number is important because engineers tend to underappreciate just how much more expensive their time is than a computer’s. A whole physical CPU core costs about 10 cents/hr on EC2! That’s three orders of magnitude less than you.

- This is a fun one from my colleague Eric Zhang. I think he was finding that we were too often treating

logger.info("stuff!")as ~free and wanted to give us a useful comparison to understand that it’s very much not free! Those CPU seconds add up when you’re emitting millions of log lines a day.

Future numbers

Down the line I’d love to add some GPU numbers into the mental toolkit. But right now I just don’t know enough about GPU architecture to handle these numbers without combining them into nonsensical results. LLM numbers such as token/s throughput and cost per token would also be interesting to have at hand.