I’ve been operating Kubernetes (using EKS) in a data engineering team for almost three years now, and I’d be wary of using it if I had the choice in the future. This isn’t an anti-Kubernetes post, as I think Kubernetes (K8s) is a game-changing technology and would bet that our team’s investment in K8s will pay off over the longer term as our engineering headcount grows past one thousand. This post is a ‘be careful, you are not Google’ type post, with some specifics on how K8s ownership has proved frustrating and unsatisfying to an engineer whose actual goal is to help the business understand itself and build better products using data & ML. (1) K8s is as complicated as people say it is, and when wielded in service of data jobs provides a few nasty foot-guns. (2) It is not tailored for ad-hoc batch jobs, and so provides a somewhat clunky user and operator experience. (3) Providing further troubles to batch job runners, K8s is not elastic, or only made elastic with difficulty, such that cluster utilization is often low. (4) Finally, in this day-and-age of cloud computing and cloud computing economics, is a fundamentally cluster-oriented system the best option? It seems possible to avoid worrying about clusters entirely. I hope this post can be both a ‘cold shower’ on the K8s hype in the data space, and encourage a shift in focus towards serverless, user-friendly data job systems.

Organized complexity

As a graduate engineer I was kind of delighted to onboard into a data team setting up K8s. K8s was sexy tech, and it provided a lot of breadth and depth to progressively master. Thirty months later though, and I must confess to some wearyness. I’ve learnt a hell of a lot, but still don’t know enough to avoid fresh trouble, and each new thing you install into the cluster provides yet more opportunity for distributed shenanigans.

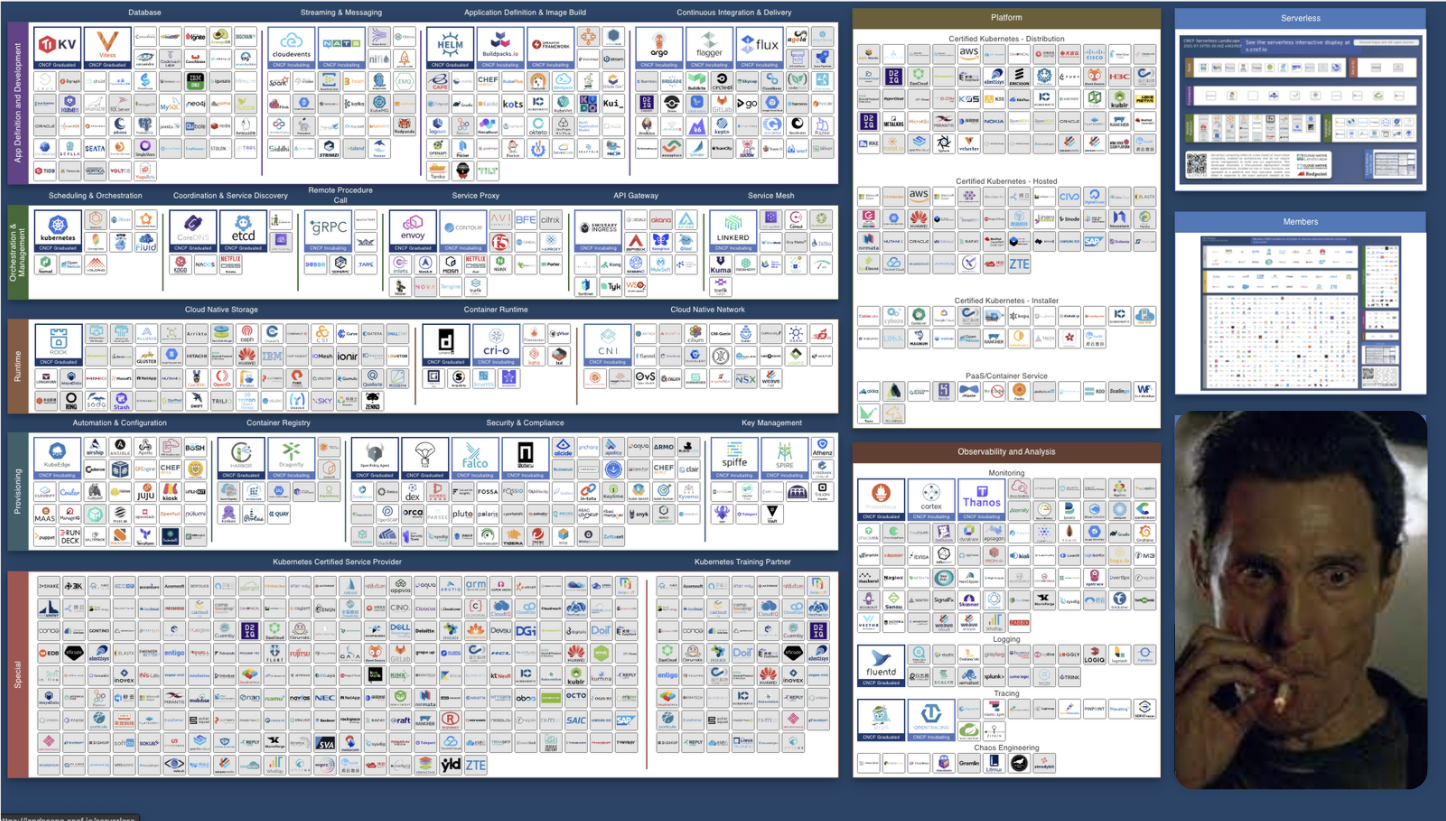

And then there’s the K8s ecosystem…

My god, the ecosystem. It is in conversations where K8s is offered in tandem with ‘service mesh’, HELM, and some five-odd security plugins that the whole thing becomes a parody.

I aspire to simple, and take seriously the rewards of persisting with only a few dull, well-trodden technologies, and the K8s ecosystem attacks these better angels of my nature. One thousand new fancy peices of tech are just a YAML apply away.

Putting your product engineers on the K8s learning curve

Good engineers will embrace a learning-mindset, but opportunity costs demand that they be deliberate about what they learn in the time they have. I have no qualms with infrastructure engineers devoting hours to learning how to operate K8s, but do worry that it’s too easy to burden a K8s cluster’s end-users, in my case product-oriented engineers, with an unpleasant learning curve. Product-oriented engineers should be maximally focused on building products. That’s their business problem. But without concerted effort on the part of an infrastructure engineer to hide K8s from the product engineer, that person finds themselves floundering without K8s knowledge. Product-oriented engineers should put their minds onto the inherent complexity of their business problem, and I usually fail to see how the complexity in K8s should be included as inherent complexity in a problem like “predict the churn propensity of foo customers using our GoldWidgets product”. K8s is no more part of that problem than understanding the Javascript V8 runtime is part of a web accessibility engineer’s business problems.

Inside the belly of the beast, you find its father, the batch job orchestrator

K8s is the descendent of Borg, which is a descendent of something called Global Work Queue, a batch job runner! Clearly not much is left of that batch job legacy, though Borg was supposely heavily influenced by GWQ. K8s is now predominantly focused on stateless application workloads such as web microservices. What we’ve got in K8s for batch jobs is CronJob and Job. But they’re a bit janky and not something you can cleanly offer to engineers.

If you’re skeptical that K8s CronJobs would be so hard to operate and provide ‘AsAService’ to your fellow engineers, Lyft’s How we learned to improve Kubernetes CronJobs at Scale provides detail showing that running Cron tasks on K8s is a whole different ballgame than the crontab, and even a Lambda function. Also read about Stripe’s experience building their “distributed cron job scheduling system”. In both cases the company’s had highly capable infrastructure teams dedicated to building up a Cron service on K8s. This is not easy-peasy, though it may sound simple.

At my company we have more or less given data engineers the CronJob capability ‘as is’ and let them have a go. Something always goes wrong, particulary if they think they need to provision a PersistentVolume (scary). Here is a small subset of the sharp edges in the raw CronJob resource type, that I came up with in under a minute:

- Submitting a job for an image that doesn’t exist. Consequence: permanent

ContainerPullBackOfferrors and job doesn’t die. - Submitting a job requesting resources that no node can fulfil. Consequence: scheduler never schedules the job so Job is permanently in Pending state.

- Submitting a job with no deadline. Consequence: Job potentially runs forever and wastes money.

- Submitting a misconfigured job with a misconfigured PVC. Consequence: PVC never goes away. Permanently paying for useless storage and clogging clusters.

If I wanted to setup CronJobs in the future, I’d first try just a dumb as rocks cron scheduler service talking to one of the cloud provider’s job services.

Batch workloads and inelastic clusters

Batch workloads by nature provide super bursty load to a compute platform. K8s is not out-of-the-box optimized for this kind of load. The managed cluster services (we use EKS) have fixed control plane management costs, so you pay something for the cluster 24/7 whether you have jobs running on it or not. It’s not at all simple to fracture your cluster into multiple instances types to support the occassional high-memory of GPU-accelerated job that you need to run. We have for at least 18 months eagerly followed issue #724 on the aws/containers-roadmap: ‘[EKS] [request]: Managed Nodes scale to 0’. Without ‘scale to zero’, each nodegroup must run at least one node 24/7, so your fixed costs can be in the thousands per-month depending on the instance types in you cluster. It’s 2021, we can do better than this.

At scale the default scheduling behaviour of K8s can wreck a batch job runner’s SLOs. Specialist batch job schedulers for K8s have been built to handle burstiness that it otherwise fails to handle.

It is not outlandish that data platforms could support a fully elastic, serverless experience to its consumers. When a job is running, the platform pays for the resources it requests (and no more), and when the job dies the costs go to $0. Just like AWS Kinesis provides a remarkably consistent experience whether your hourly throughput is measured in megabytes of data or terabytes, could a batch job plaform not be consistent in its experience and price efficiency whether you’re requesting 1GB or 1000GB of RAM?

I think we could enjoy a platform like this, but that platform is far from out-of-the-box K8s.

Clusters?! Where we’re going…

It’s 2021, we should have a good serverless batch processing service by now, and be happy using it. AWS S3 showed that you can have ridiculously scaleable and reliable blob storage with a sane API, and I think that data infrastructure folks should look to it as a model of what we deserve.

With K8s, you run and operate a crapload of software so that you can have your cluster users just command: “Give me 10 vCPUs, 500GB of RAM, and 100GiB of disk space to run this container image.” As a platform user experience that’s a great start, but unfortunately for a K8s operator it’s still their job to wrangle a group of VMs to make sure those resources are available and prevent scheduling errors. The data engineer becomes the sys-admin. That sucks.

A major recent success story in the serverless data platform space is Snowflake data warehouse. As a warehouse operator, you deal not with EC2 VMs but with t-shirt sized ‘warehouses’. Thanks to decades of SQL query engine development, Snowflake can let you ‘turn the tap on’ and execute a fat query over terabytes of data all without thinking about milliCPUs, RAM, disk, network, scheduling, VMs, Docker. That’s their problem, you just hand over the SQL query and the money.

Could you imagine if your whole business was making it easy for anyone to just throw money at a problem? Fucking legends.

— Josh Wills (@josh_wills) September 17, 2021

Now general batch compute platforms accepting Docker images from whomever don’t quite have it so easy as this, but we know it’s possible to make K8s problems headaches for well-paid cloud services engineers. We use Github Actions, Google Colab, and AWS Lambda all the time these days. The ingredients are all there, they’re just arranged inappropriately or wrapped in totally oblique UX:

HELL YES. @awscloud has released a Serverless service that runs Docker containers as cron jobs. FINALLY!

— Corey Quinn (@QuinnyPig) July 16, 2020

There's nothing to manage, it only charges you when it's running, it has tagging and CloudFormation support...

(read through that whole thread to learn about AWS’s secret batch job service)

A possible serverless data future

A better future will see data infrastructure providers, whether internal or external, completely abstracting away what engineers don’t need to care about, keeping their focus on what’s essential. For a while now the industry has had data professionals considering their wheelhouse “Python(3), and some packages I install with Pip”. This works up until a point, after which things fall apart, but we have the cloud computing services and software engineering smarts to safely bring code complexity back close to this point. At least, much closer than:

“Build your program into this Dockerfile, then write this YAML to specify a Job. If you get it slightly wrong, your job won’t run at all. If it runs for a bit and then breaks, to see how it broke, use this CLI called kubectl.”

I think the key features of this better future would be:

- A K.I.S.S cron scheduler service. It baffles me that Google Cloud and AWS make cron scheduling a container so annoying. Read ‘Creating and configuring cron jobs’ and it seems sensible until you get to “job’s target” and it doesn’t list a fucking container as an option.

- Resources, not VMs. Don’t make users pick instance types. The default K8s

requestandlimituser interface is fine, actually. A company’s data engineers just shouldn’t have to wrangle the pile of VMs facilitating that interface. - Data architecture best-practices made obvious. K8s made it hard to build non-stateless applications, because it came in with the wisdom that stateless is the way. For data, we have similar wisdom with which to imbue our platform systems.

- Data batch jobs can be mostly modelled as a transform function over some structured input data, so the batch job platform should encourage that kind of problem decomposition.

- Idempotency should be a first-class concept, as well as dataflow.

- Be opionated about best-practices like dry-run testing, staging areas.

- Don’t wrap the cloud system in so much YAML and cloud services minutae that a local-prod impedence mismatch destroys our tight dev loops. I should not need to run a mini-container orchestrator on my laptop to test my pipeline changes.

Conclusion

Now this is like the thousandth ‘beware K8s’ post, and maybe the hundreth one of those specifically about batch job workloads, and I’m betting it won’t be the one that convinces a K8s virgin to put down the cluster and just pay money to a cloud giant. But I’ve at least put down my personal feelings, as a kind of psychological exercise in moving on. I don’t want to say again:

“I’m a data engineer, but we recently took up Kubernetes, so my main problems these days are YAML, PodDisruptionBudgets, ContainerPullBackOffs, RBAC, …”